[Article] 'Yonsama'(37): Korean love god captures Japanese hearts.

Cr. - http://www.koreatimes.co.kr/

By Andrew Salmon

Actor Bae Yong-joon leads ‘hallyu’ (Korea wave).

Some years ago, this writer climbed into a taxi in Seoul. As is commonly the case, the driver asked where I was from. On hearing “the United Kingdom,” he responded, “Aha! Beckham!” Then, in excellent Konglish, he continued, “U.K. — David Beckham! Korea — Bae Yong-joon!”

For a moment, I was nonplussed. I was about to respond, “No my good man, Bae is a thespian, not a footballer” when the penny dropped. Bae was to Korea what Beckham was to the United Kingdom: an international sex symbol.

While the United Kingdom has had its share of male superstars dating back to the days of John, Paul, George and Ringo and the “British Invasion,” this was a novel experience for Korea, a nation that had previously been known more for exports of supertankers than dreamboats. Moreover, Bae’s fame had ignited in — of all places — Japan, the nation that had, for most of the 20th century, had a problematic relationship with Korea.

The vehicle that conveyed Bae to super-stardom was inauspicious. “Winter Sonata” in 2002 was a do-it-by-the-numbers Korean soap opera; a “no-sex-please, this-is-pure-love” romance that plays out to the tune of syrupy ballads and features only drop-dead gorgeous actors and dreamy locations, as well as that classic (and much-used) device of the Korean melodrama, a character who loses his memory.

In short, this was no downbeat, day-to-day soap of ordinary people a la “East Enders” or “Coronation Street.” This was romantic fantasy. The series was a hit in Korea and across the region, but its real explosion of popularity — an authentic phenomenon — would come across the East Sea.

This was remarkable as relations between the two neighbors in the 1990s had been particularly prickly, with historical and territorial disputes rising again and again and again. There had been amity and cooperation — but also suspicion and competition — during the jointly hosted 2002 World Cup.

Arguably, “Winter Sonata” would do more to inch the nations closer together than the world’s most popular sporting event.

Korea conquers Japan

The show’s main fans were love-lorn Japanese housewives of a certain age. So keen on “Winter Sonata” was this sizeable population segment that the series repeated twice in the same year on NHK. Social critics, taken by surprise by its runaway success, speculated that while Japanese TV had become more sophisticated in its productions, this Korean import was a throwback to a simpler, kinder and gentler era.

A “Winter Sonata” boom resounded across Korea. Eager Japanese housewives flooded the nation on tours to visit the filming locations and, of course, drop yen in the boutiques and department stores that queued up for “Winter Sonata” stars to endorse their outlets and brands. Japanese tourist numbers surged; extra flights were reportedly scheduled to keep up with the demand.

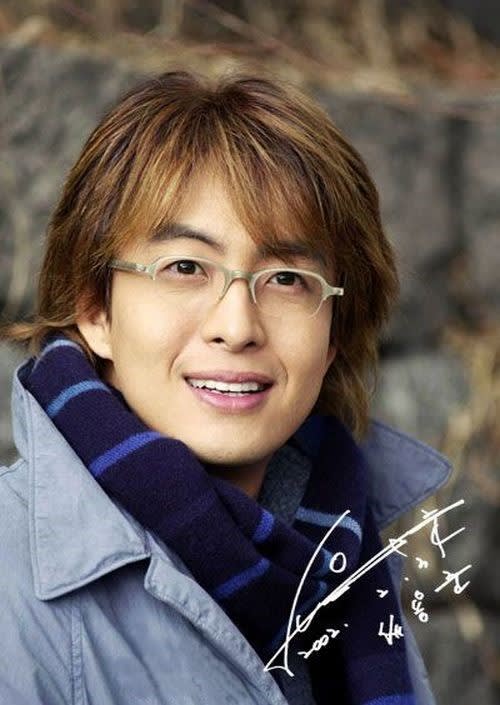

But while Korean travel agents — not to mention canny marketers, merchants and merchandisers — raked it in, it was Bae who was the big beneficiary. In the series, he had played the lead male role, the Prince Charming. Beholding his smooth skin, gentle smile, bespectacled eyes and (not least) his carefully knotted muffler, Japanese matrons swooned en masse.

Bae’s fame rocketed. He appeared as a host on Japanese TV; he was approached to endorse products, open restaurants, pen books. At summits, he was cited and mentioned by Japanese prime ministers and Korean presidents alike. When he landed at a Japanese airport to promote another TV project, the scramble to see him was so desperate that a number of fans were injured in the crush. According to reports, Bae sportingly paid their medical costs.

Koreans had been leaned on to take Japanese names near the close of the 1910-1945 colonial era, but when Bae was re-christened “Yonsama” (“Prince Yong” after the actor’s first name) by Japanese fans, nobody minded. This was not coercion, this was an honor.

For the first time, a Korean was a sex symbol in Japan. There had been nothing remotely like it since “Rikidozan” the star of 1950s Japanese pro-wrestling. But Riki was not nearly so wholesome a figure as Bae. He was a tough guy rather than a sex symbol, and anyway, he had promoted himself as Japanese, keeping his Korean ethnic identity close to his chest. Bae had no reason to do this; he was unabashedly Korean.

Wave rolls on; Bae left behind?

The term Korean wave (“hallyu”) had been coined in China in 1999, and is generally believed to date back to the slick action blockbuster “Shiri” which came out that year. “Winter Sonata” was the first monster-hit soap opera. It would be followed by other Korean melodramas; the next biggie, which took the region by storm, would be 2003’s “Daejanggeum” (“The Jewel in the Palace”), a costume drama about a Joseon-era royal chef. From then on — and in sync with a corresponding crescendo of Korean popular music — the Korean wave surged ever onward and ever outward.

Bae spent increasing time on lucrative product endorsements, but continued to work in dramatic roles. His first major post-“Sonata” role was a departure: He appeared in (and out of) Joseon-era costume in a racy 2003 Korean remake of “Dangerous Liaisons” entitled “Untold Scandal.” The film, which was R-rated in Japan for its steamy bedroom scenes, scandalized a number of his fans, who had preferred the romantic gentleman of the soap opera to the conniving, shag-happy cad of the film.

He later appeared in the more conventional TV historical epic “King Gwanggaeto” in 2007. But no succeeding projects won the headline success of “Winter Sonata” abroad, and Bae may have been irreversibly typecast. Perhaps due to the reception to “Untold Scandal,” his 2005 movie “April Love” had been a tender “Sonata”-style love story.

While Bae’s English language website boasts of his versatility — “he always comes to us in different ways” — it prominently features love ballads and the main photos are a selection of the kind of smiling, cutesy image fans so loved from his most famous drama. According to news reports, although he can command $5 million per picture, other Korean actors can now demand double that.

His image has also been called into question. His smiling public persona was as Mr. Nice Guy, but local entertainment reporters alleged that he had a mercurial temper and was not above dishing out physical violence when displeased with managerial decisions. (His site lists his hobbies as weightlifting, hapkido and kendo.)

And he suffered from stress. Bae admitted to reporters that he was suffering a crisis stemming from his popularity. Unable to go out in public, his life was a constant shuttle between home, the office and (of course) the gym.

Yet rumors of violence did not impact his image and fears online and in popular media that he might commit suicide — the fate of one of his “Winter Sonata” co-stars in 2010 — proved happily unfounded.

Yonsama: icon

Today, the Korean wave has spread far and wide. Posters of Korean actors, actresses and musicians are plastered over the bedroom walls of teens and 20-something funksters and hipsters across Asia and beyond. It is soaps — along with K-pop — that make up the bulk of the wave; movie exports (which tend to be edgier and less formulaic then dramas and music) are a distant third. “Winter Sonata” was the first Korean super soap, Bae its superstar.

Like Beckham — who could never be described as one of the world’s greatest football players, but who has won fame as a global male fashion icon — Bae may never be recalled as one of Korea’s finest dramatic talents. However, his chiseled bod, smooth-faced good looks and dazzling smile cannot be denied. These are the assets that ensure his place in the history of pan-Asian popular culture: Yonsama was Korea’s first international sex god.

Andrew Salmon is a reporter and the author of three works on modern Korean history — “U.S. Business and the Korean Miracle: U.S. Enterprises in Korea, 1866 — the Present,” “To the Last Round: The Epic British Stand on the Imjin River, Korea, 1951,” and “Scorched Earth, Black Snow: Britain and Australia in the Korean War, 1950.”

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.